Differentiation is a funny old word isn’t it? Let me be clear from the outset: I am absolutely not for the abolition of differentiation, but, I strongly believe it’s something as a profession that we wildly get wrong or mistreat. All with the best held intentions of course, but the nagging worry in my head is that it can cause more harm than good. This is a blog that’s been brewing in my head for ages since I saw the following exchange on EduFacebook:

Mrs Teacher: Hey guys, got to teach about relative clauses in a lesson observation and need to find a way to differentiate this between HA, MA and LA.

A Genuine Response: Perhaps the LA could just look at them but not use them.

A bizarre idea, I thought and one I’d have no idea how to react to as an observer. I always like to use PE as an analogy when thinking of things like this, and that would be the English lesson equivalent of showing a child how to bowl a ball and then never letting them hold one and have a go themselves.

One of the biggest myths in education, and one I was certainly taught on ITT and arrived in the classroom believing, is that children fit into three neat groups of differentiation. Some are high ability, some are middle ability and some are low ability. In actual fact, if you’ve got 32 kids in your class, you’ve got 32 ability groups. Not to mention that their ability changes based on what you’re doing (those good at number may not be gifted at shape; your natural storyteller might not be able to concisely impart information in a scientific report), what mood they’re in, what they had for breakfast, how many hours sleep they had, how much they understood it yesterday, how long you explained it for or what happened at playtime. The list of things that affect performance from lesson to lesson are endless.

And yet, we see chilli challenges in maths, the idea that some children need to live on a diet of easier books because they aren’t natural decoders yet and even the idea that you need to differentiate history three ways (usually based on a completely pointless three way splitting game of ‘who is the best writer’). Often this is done with the aim of closing the gap and making sure that children can keep up with their peers. Sadly, when you give one group easier work and one group harder work, you literally sit and plan to widen the gap in your class, and that is exactly what will happen. The better will get better and the weaker won’t get near them. As Bart Simpson once said ‘so we’re going to catch up…by going slower than they are?’

I’d like to add a small disclaimer in here, that sometimes there are children, with no alternative provision to go to, who genuinely cannot access their year group’s work. We should, of course, find a way to cater for these children in the most inclusive way we can (and hopefully get them doing a bit of their year group’s work), so I am not saying ‘let’s bin off differentiated activities for everyone’, like every hot topic in education, throwing the baby out with the bathwater wouldn’t do anyone any good.

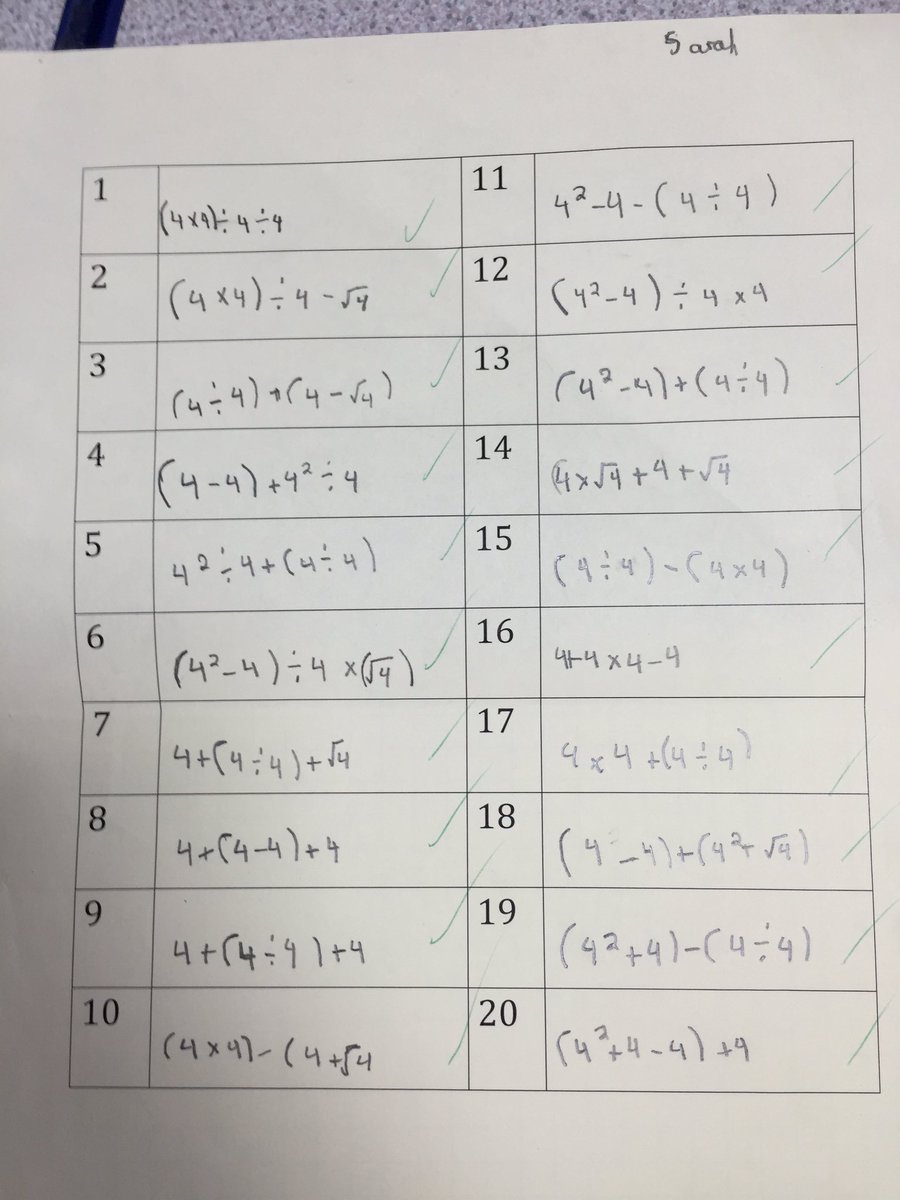

However, with the above said, I’m a big believer that the children should access their year group’s curriculum, work on the same objectives, and, for the most part, access the same activities. Take the example activity below: I do this with Year 6 every year. Everyone does it. Some children relish the challenge and get straight on with it. Some need me to show them a way in. Some go to bits and I spend ten minutes reteaching BODMAS. Everyone does it. Does everyone finish it? No. Did they need to? No. Did the typically lower attaining children access it and deepen their understanding of BODMAS much more than they would have if they’d just sat and done calculations making sure to apply the formula? Of course they did.

I even loathe to use the words ‘typically low attainer’ because what does it even mean? In everything? Just in maths? In all aspects of maths? It’s just wild conjecture to box a child up and say ‘this is how they achieve so make sure you teach them to that level’. It’s a ceiling on learning that we should strive to avoid at all costs.

So how do we differentiate if not by giving out different activities? There are a plethora of ways. In maths, based on the lesson before, I would potentially have some pre-teaching going on with the LSA (yes, I’m lucky to have one and know not everyone has the same luxury). I tell her exactly how I’m going to teach it, she teaches it, they come back in and I teach it them again. This almost always gets them hitting the ground running. We do daily fluency in maths and English that we try and link into what we’re doing (so if we were simplifying fractions, my fluency work might be heavily division/factor/multiple based and I could identify anyone who’d potentially struggle with that and move them onto the same table). We can give resources out of course, when we get to doing long multiplication in Y6, I can’t think of a year I haven’t given at least one child a multiplication chart, because I want them to learn the method and we can keep plugging at the retention of table facts and conceptual understanding of what multiplication is in well needed intervention time; however, if they just spent that lesson trying to learn table facts, when would they get to practice long multiplication? When would they get to be on a level with their peers? In writing, some children may need a structure strip and some might not. Some people just struggle to organise their thoughts more than others (I wish someone had done me some structure strips for this blog). In whole class reading sessions (I still strongly believe children need a personal reading book ‘at their level’) you can read the text to the children who might struggle. When we restrict children to low books all the time we can’t be surprised when they don’t catch up. It’s like giving one table one paragraph about tortoises and everyone else a whole chapter and then being surprised when the table with one paragraph know less about tortoises than everyone else. It is our responsibility to find ways to stretch and challenge the children and try and get them to perform at the expectations for their age.

The majority of differentiation we do is invisible. It’s in the subtle difference of the question we ask Kaden compared to James. It’s in the way we circulate the class but make a point of looking at Aisha’s book slightly more than Miriam’s. It’s in the way we read both Nathan and Ryan’s books, but know from the day before that Nathan will have found it easier to access so may have done some more high level stuff.

I like to use a slope of difficulty in most lessons. So if I were teaching about percentages of amounts I would have the children just do a few fluency questions on it, a little bit of reasoning (usually ‘why is this wrong?’) and then fluency/reasoning/problem solving activities that gradually get harder. The best example of what I mean is below (though missing the fluency). These activities would just be at the back of the room and the children would move onto the next one as and when they were ready (helping me and the LSA to know where to direct our attention as we both circulate the room: we do not work with groups). This means all the children have access to all these activities; not ones I decided would work for some groups beforehand, potentially limiting what some children could do. Granted the work below is a child that found percentages very accessible; however, were we doing properties of shape tomorrow they would find it very difficult. With the exception of the last task, which was for those who you could see in the lesson well and truly ‘got it’, all children were exposed to and expected to do the other tasks, even if this meant stopping the lesson and moving them onto it, or simply going through it at the end.

This can work for English lessons, but they tend to be more ‘here’s a type of grammar/punctuation/construct, let’s all practise it in a paragraph now based on this stimulus’. If you have a great way to ‘stretch’ those who really get it in an English lesson of this nature then I’d love to hear it.

In summation, differentiation is good. It’s necessary. It’s a brilliant wonderful tool. But let’s use it to get everyone on the same patch of grass, rather than everyone working in a different field. And don’t get me wrong, I’m not saying I’m getting it right (and I’m certainly not 100% of the time) and others are getting it wrong, but perhaps it needs a long overdue rethink.